digital id cards: what the UK can learn from estonia and spain

Compare how Spain, Estonia, and the UK are building digital ID systems – and why Estonia’s trusted approach is the model others can learn from.

When I first arrived in Spain, digital ID was not a concept on my radar.

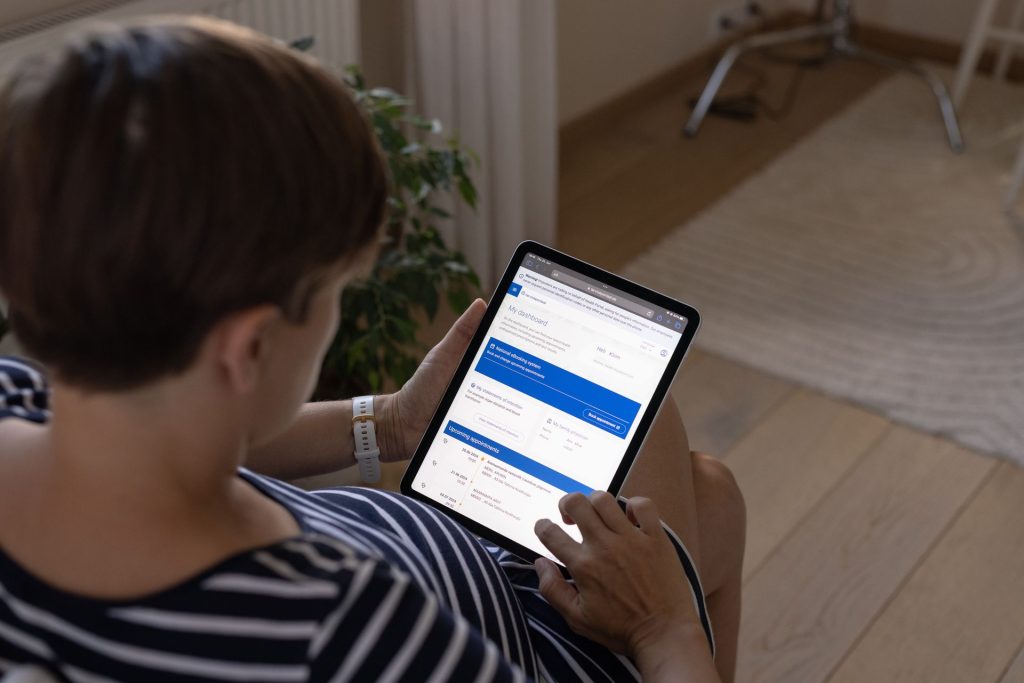

What is a digital ID used for?

Adam is part of the e-Estonia team consulting on the UK’s proposed ID card adoption.

Spain: Modernising identity for convenience

Maybe I am just biased, but I know that things can be so much better!

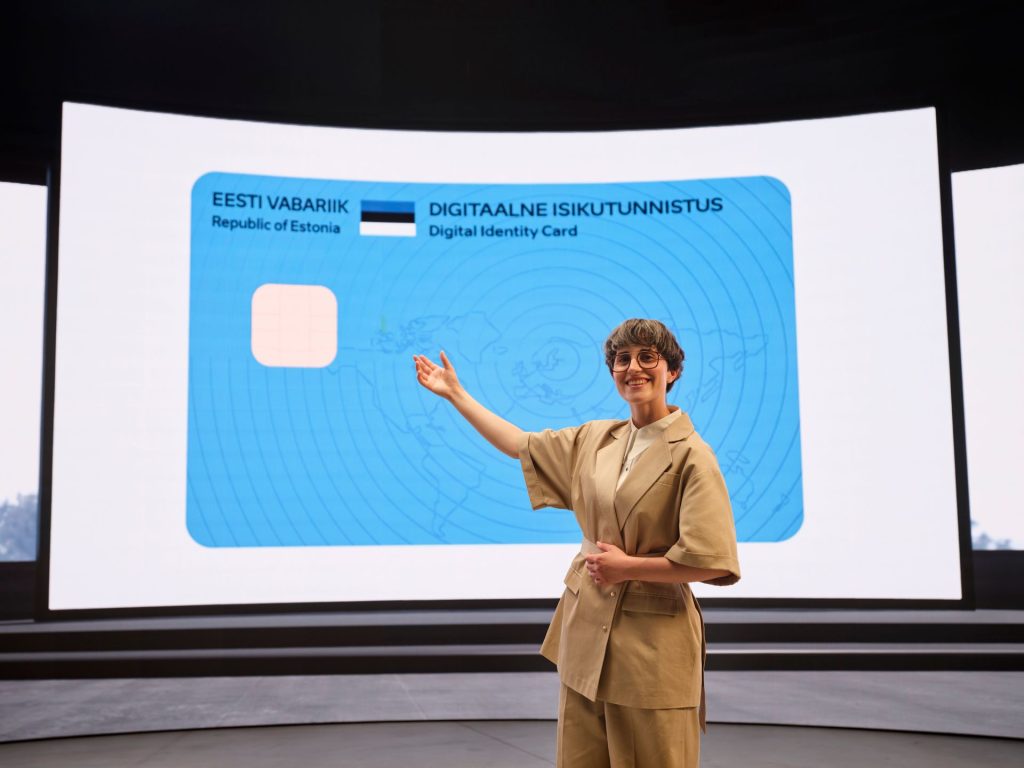

Estonia: A trusted model for digital governance

Watch how e-identity works in Estonia:

Estonia’s digital ID stands out for:

The downsides of digital ID

Digital IDs and freedom

Comparing approaches to digital ID

There’s a lot of work still to do.

Looking ahead to a digitally enabled future

More from e-Residency

- Sign up for our newsletter

- Watch fresh video content - subscribe to our Youtube channel

- Meet our team and e-residents - register for our next Live Q&A